-

Appeals Court Upholds Jury Award To Sculptor For Copyright Infringement

03/28/2017

Earlier this month, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a $450,000 jury award in a case against a businessman who commissioned knockoff copies of several of the artist’s sculptures.

Earlier this month, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld a $450,000 jury award in a case against a businessman who commissioned knockoff copies of several of the artist’s sculptures.

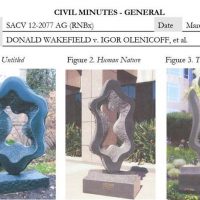

The plaintiff in the case, California artist Donald Wakefield, is known for his large-scale stone and metal sculptural works, each of which is one-of-a-kind. According to court filings, in 2004 he contacted a handful of real-estate developers whom he believed might be interested in purchasing some of his sculptures. Hprovided these prospective buyers with information about his work, and he pointed them toward his website displaying photographs of his creations. One of the businesses he solicited was Olen Properties, owned by billionaire Igor Olenicoff.

Fast-forward a few years, and Wakefield claims that in 2008, he discovered a copy of one of his pieces at a property owned by Olen Properties; he believed, however, that he must be looking at the original (which he had not seen since the early 1990s, when he gave it to someone in Chicago as a gift). In early 2010, he discovered two more copies of the same work, as well as one derivative of the work, at a different Olen Properties location. At this point, he says, he realized that these were infringing copies, not his original work. He ultimately learned of other knockoffs on display at a third Olen Properties location, bringing the total to seven. He sued Olen and Olenicoff in 2012, asserting copyright infringement and related federal claims associated with the allegedly infringing pieces. His lawsuit argued that Olenicoff had arranged to have the knockoffs manufactured in China rather than pay for Wakefield’s real work. For their part, the Olen defendants claimed that when they bought the sculptures from a Chinese artist, they were unaware that the works were similar to Wakefield’s.

In federal district court (see Docket No. 8:12-cv-02077-AG-RNB (C.D. Cal.)), the Olen Parties prevailed in part on summary judgment, eliminating Wakefield’s claims regarding the first artwork he had discovered in 2008, on grounds that claims regarding that piece were untimely under the three-year statute of limitations for copyright claims. Wakefield’s remaining claims for damages and injunctive relief related to the other six works were tried before a jury in 2014, resulting in a $450,000 award to Wakefield. The district court entered judgment for Wakefield, but granted the Olen Parties’ motion for judgment as a matter of law as to the jury’s award of actual damages, ruling that there was insufficient evidence to support the jury’s award. Thus, the district court left Wakefield with a somewhat pyrrhic victory: a judgment that he had been the victim of copyright infringement, but that his case had not adequately proven his monetary damages. (As some consolation, the court did order that the Olen parties either hand over the infringing works to Wakefield, or have them destroyed; the defendants opted for the latter.)

Both parties appealed to the Ninth Circuit, where Wakefield challenged the district court’s rulings on the statute-of-limitations and damages issues, and the Olen parties argued that all the claims should have been time-barred and that the injunction ordering them to hand over or destroy the works was unwarranted. (See Docket Nos. 15-556649, 15-55675 and 15-56137 (9th Cir.)). But the Ninth Circuit sided with Wakefield. In a short, unpublished disposition issued earlier this month, a unanimous three-judge panel ruled, first, that none of Wakefield’s claims were time-barred, including his claims regarding the first work he discovered in 2008; the court concluded that a “reasonable jury could find that Plaintiff had neither actual nor constructive knowledge . . . that the first sculpture was a copy” and not the original of his work. The appellate court also held that the plaintiff’s evidence of damages was “non-speculative” and that, based on the evidence at trial, a jury “could have determined that the actual use made by Defendants of Plaintiff’s work was worth $75,000 per infringing copy.” Further, the panel upheld the trial court’s exercise of discretion in ordering the infringing sculptures to be destroyed.

The case illustrates some of the challenges that face independent artists who believe their work has been ripped off. One major challenge, of course, is discovering the infringement in the first place; as this case shows, an artist may not learn of the infringement until years after it occurs, which can leave room for a defendant to argue that claims are barred by applicable statutes of limitations. Moreover, many artists may lack the resources to pursue costly, drawn-out litigation (often against deep-pocketed corporate defendants); consider that here, Wakefield’s suit took more than four years to wind its way through the process, complete with a jury trial and appeal. For those artists that do undertake a lawsuit, a further challenge for many is proving actual damages; even where a defendant blatantly infringed, a plaintiff must put forth a theory of actual damages that is sufficiently clear, supported by evidence, and non-speculative to survive judicial scrutiny, a tall order for emerging or struggling artists who may have trouble satisfactorily proving the fair market value of their work or what it might have cost a defendant to license that work. Nevertheless, this case ended in a victory for the artist, and serves as a reminder that the challenges for artists are by no means insurmountable. Moreover, such cases can have a ripple effect for a defendant; Wakefield’s suit apparently drew the attention of another artist, John Raimondi, who discovered that the Olen defendants had also copied some of his metal sculptures; Raimondi eventually won $640,000 in damages, and ultimately reached a settlement that allows the defendants to display the works as long as they’re credited as being inspired by Raimondi. Parties looking to save money by commissioning knockoffs instead of paying artists for their original work are taking a significant legal risk that may cost them in the long run.

Art Law Blog